So, how did we get here? And why is it just so darn tricky to stick to our resolutions? Let’s step back in time and explore just how this tradition works.

A Brief History of New Year’s Resolutions

Where They Began

According to the History Channel, New Year’s resolutions date back roughly 4,000 years, to when the Babylonians — a population living in what was then Mesopotamia — commemorated the new year in March, when the season’s crops were planted. The celebration consisted of a 12-day festival called Akitu, when either a new king was crowned, or loyalty to the existing monarchy was renewed.

But it was also a time for the Babylonians to make certain promises — things like settling debts and returning anything that wasn’t theirs to its proper owner. Maintaining these resolutions, they believed, came with karmic retribution, in that kept promises would be rewarded with good fortune in the following year.

The Romans are said to be the first to create the concept of January 1 and designate it the first day of the year, beginning around 46 B.C. The name of the month is rooted in Janus, a god of particular importance to the Romans, due to his two-faced nature. It was believed that Janus could use his two faces to both look back on the outgoing year, and forward to the next one. Similar to the Babylonians, Romans made vows of good deeds to Janus before the new year arrived.

Where They Are Now

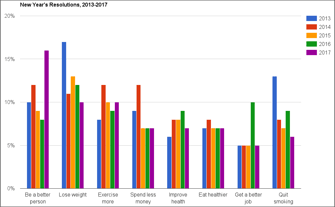

Each December, the Marist Institute for Public Opinion measures the most popular resolutions for the coming year. Starting with the top resolutions for 2017, we worked backwards to see how these resolutions have evolved — or not — over the past five years.

We’ve certainly seen a shift in resolutions since the Babylonian and ancient Roman era — going from good-doing to mostly self-improvement. However, 2017 is seeing a bit of a shift back in that direction, with more looking to “be a better person” this year.

It should be interesting to observe if that new trend influences the typical marketing response to New Year’s resolutions, and what — if any — shift we’ll see from campaigns aligning with “classic” resolutions to ones that attempt a deeper sense of self-improvement.

But there’s some intricate psychology between our resolutions and the way brands respond to them. In her book The Psychology of Overeating: Food and the Culture of Consumerism, psychologist Kima Cargill explores how, when it comes to goals like diet and exercise, there’s a human tendency to consume a larger number of things that we believe are a means to an end. Rather than trying to “locate purpose in [our] life,” Dr. Cargill writes, “shopping, spending, and eating are all part of the frenzy of consumption that has overtaken our culture.”

Cargill elaborates on one particular client as an example, citing that person’s thousand-dollar spending on a personal trainer, top-of-the-line juicer, high-end fitness attire, and specially branded health food in response to her resolution to lose weight. That client, by the way, ultimately fell into a pattern of abandoning her resolutions and starting them over again. Sound familiar? I know it does to me.

That behavior reflects what Cargill believes is an “underlying belief that consumption solves rather than creates problems,” and brands respond in kind. We see an uptick in campaigns from fitness and weight loss brands every January, leading to an uptick in new gym memberships — 67% of which go unused. And with so many people resolving to lose weight year after year, some brands have become extremely skilled at convincing us to…

COMMENTS