This in turn kickstarted the Industrial Revolution, about 250 years ago and Information Revolution, about 50 years ago. Eventually, machines could replace most types of jobs -- including roles where the worker has to make decisions based on limited amounts of information, not just routine and predictable human labor. Brynjolfsson and McAfee argue that the main driver of this inequality in income is the rapid downward pressure on wages for jobs that are being fully or partially replaced with automation. But in today’s market, there’s no reason to use the second-best fact-checking software when you can access the best. Another potential solution is the negative income tax. This system provides a minimum income while incentivizing people to work. Research by Brynjolfsson and McAfee shows that people still stay productive if a negative income tax is in use. A universal basic income or negative income tax could: Allow people to pursue work that has traditionally not been compensated well in a capitalist economy, such as community-building and social work. Under a Negative Income Tax system, a person earning below the cutoff point will get a certain percentage of that difference from the government. The Way Forward As technology continues to progress, more traditional jobs will be threatened by automation.

In 1931, at the height of the Great Depression, British economist John Maynard Keynes published the essay, “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.”

Keynes concluded that the Depression was only temporary and predicted that by 2030, people would work no more than 15 hours a week, devoting the rest of their time to leisure and culture.

Keynes was right about economic growth recovering, but most of us work far more than 15 hours a week. We’re still living in a time of over-rapid changes. Technological innovation has fundamentally changed the way we work, but are we really moving toward a society where humans are free to pursue culture and leisure while enjoying an age of abundance?

We Are Living in An Unprecedented Age of Change & Progress

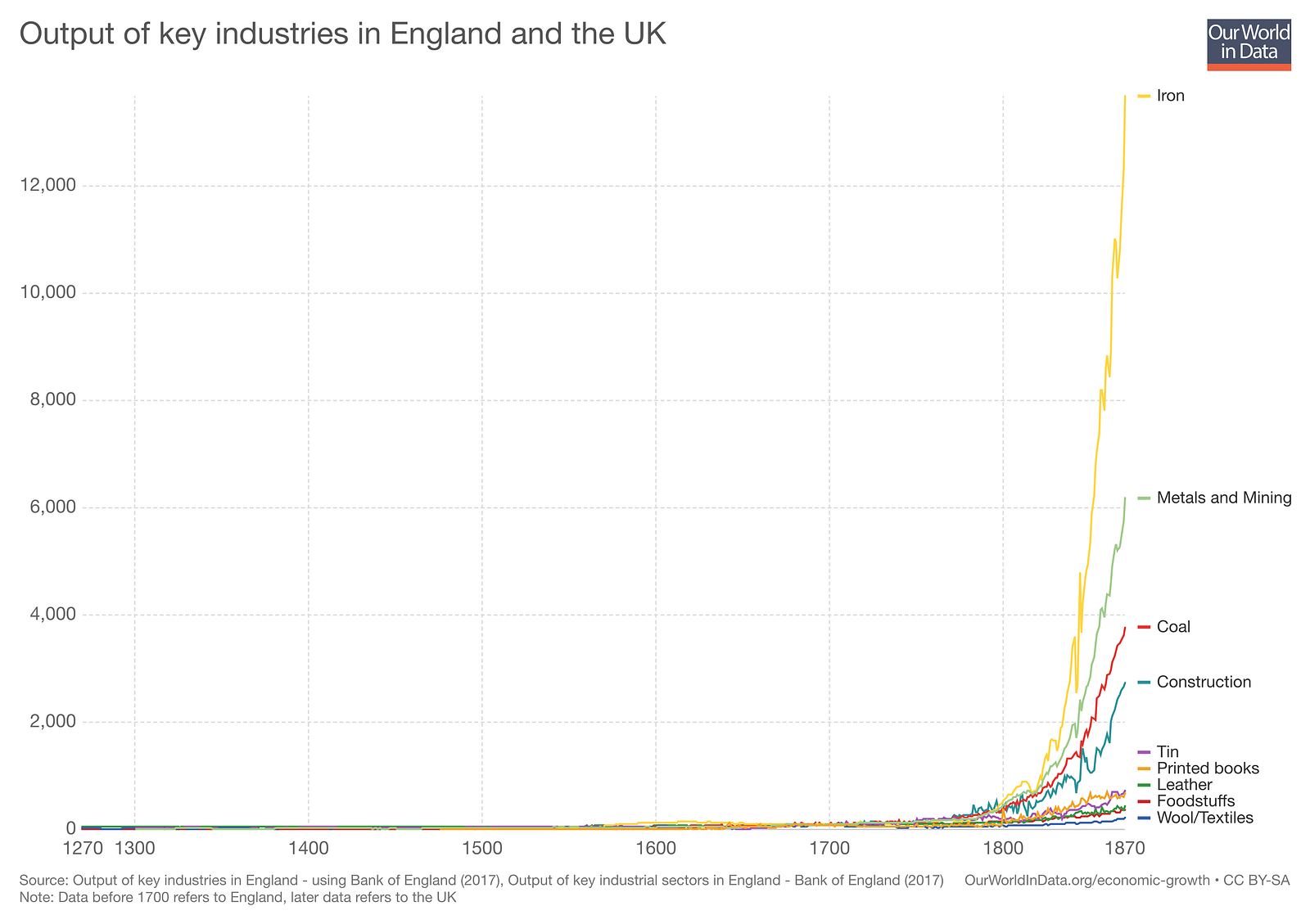

For the majority of human existence, we’ve made progress at an unremarkable pace, but in the last 80 years, as this chart shows, progress has exploded.

Human progress can be marked by five significant revolutions, the most transformative of which occurred 50 years ago, as Yuval Noah Harari wrote in Sapiens. First was the Cognitive Revolution; about 70,000 years ago, we invented language and started to preserve knowledge. Then came the Agricultural Revolution; about 11,000 years ago, we transformed from nomadic tribes to town and city dwellers after we learned how to harness the power of nature to farm instead of forage for food. The Scientific Revolution brought Europe into the age of imperialism and rapid expansion about 500 years ago. This in turn kickstarted the Industrial Revolution, about 250 years ago and Information Revolution, about 50 years ago.

Each time human history jumps forward, we’ve replaced countless jobs by inventing ways to do them better: The farmer replaced the hunter, steam engines replaced human workers. At every single point, such inventions have coincided with rapid economic growth, making the lives of humans better off as a whole.

Even though we’ve demonstrably been good at replacing ourselves with machines, we still pride ourselves on being the best thinkers and decision makers on earth. Because while machines could help a farmer increase his crop yield, the ultimate decision on what to sow and when to harvest still lies on him.

We believed we were the best thinkers and fastest learners on earth. But it’s no longer true.

In 2016, history was made when AlphaGo became the first computer program to beat the highest ranked professional Go player, Lee Sedol, without handicaps. One reason this was so impressive is that Go is considered much more difficult than other strategy-based board games, with over 250 possible opening moves compared to chess’ 20.

Machines are rapidly replicating (and improving upon) our previously unique ability to learn quickly and make decisions in reaction to changes in our environment. Eventually, machines could replace most types of jobs — including roles where the worker has to make decisions based on limited amounts of information, not just routine and predictable human labor.

It’s Hard for Humans to Predict Technological Change

If someone invented a time machine and transported an ordinary person from the 16th century to the 18th century, she would not, for all intents and purposes, have a hard time understanding the world. The same would not be true if someone was transported from the 18th century to the 20th century — technology has changed so quickly that she’d probably think she’d been brought to a different universe!

The changes in outputs of key industries created a drastically different worldThe changes in outputs of key industries created a drastically different world.

In the same vein, if you asked a factory worker from the 1970s if he believed that machines would eventually put him out of a job, he would find the question hard to understand, let alone answer. That’s why we must constantly question our understanding of the rate of technological progress and acknowledge that the vast majority of us are ill-equipped to make sense of it all.

It’s estimated that as much as half the world’s labor could be automated over the next 20 years. There are two potential outcomes of this massive disruption of the labor market:

(1) an era of mass unemployment and social instability, or

(2) an age of abundance where we are free to pursue creative work

Scenario 1: An Era of Social Instability

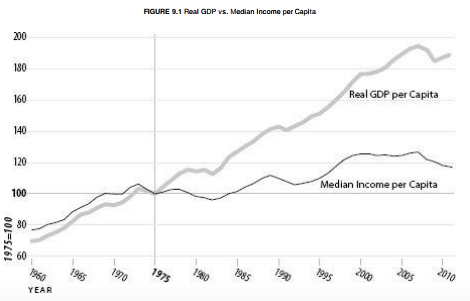

In 1990, the real inflation-adjusted income of the median American household reached $54,932, but then started falling. By 2011, it had fallen nearly 10%, even as overall GDP hit a record high, according to The Second Machine Age by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee.

Source: The Second Machine Age

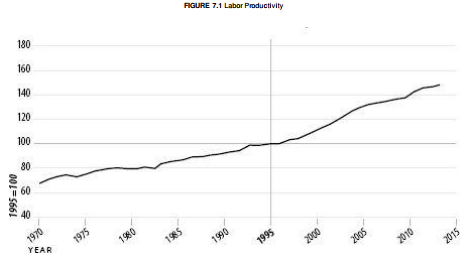

In contrast, productivity grew at an average of 1.56% per year during this period, and most of this growth directly translated into comparable increases in average income. Brynjolffson and McAfee argue that median income shrank because of increases in inequality.

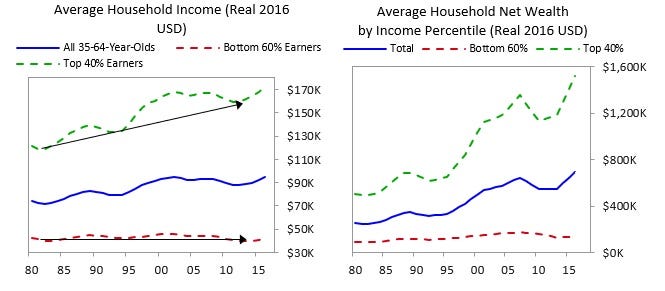

Source: The Second Machine AgeRay Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates , came to the same conclusion. In October 2016, Dalio evaluated the US economy by separating it into two cohorts, the top 40% and the bottom 60%.

He found that the average household in the top 40% earns four times more than the average household in the bottom 60%. While the bottom 60% has experienced some recent income growth, real incomes have been flat to slightly down since 1980 (in the same time period, income has increased for the top 40%). Those in the top 40% now have on average 10 times as much wealth as those in the bottom 60%.

Brynjolfsson and McAfee argue that the main driver of this inequality in income is the rapid downward pressure on wages for jobs that are being fully or partially replaced with automation.

For example, if one hour’s worth of human labor can be done by a machine for one dollar, then under a free-market system, profit-focused employers won’t offer a wage of more than one dollar. That worker will need to settle for lower wages, and could be laid off entirely.

Because digital technologies can replicate innovative ideas at low cost, a person who finds a way to leverage them will earn exponentially more than has been possible –what Brynjolfsson and McAfee call a “winner-take-all” market. For example, a relatively small number of designers…

COMMENTS